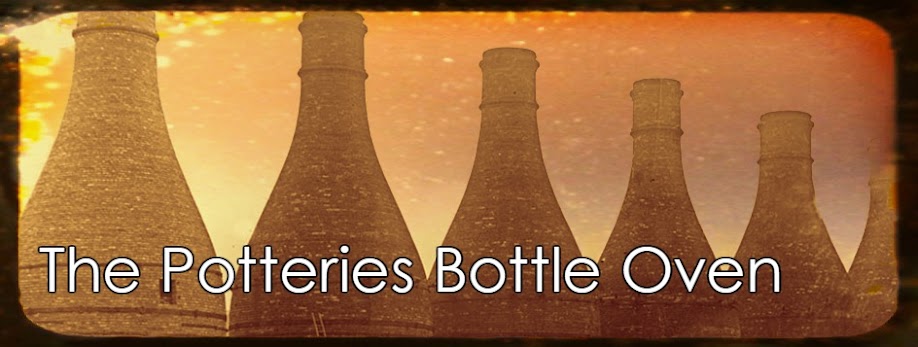

The dominant and characteristic feature of the Potteries for over 250 years

Put simply, a potter's bottle oven is a 2-part brick-built, bottle-shaped structure up to 70ft high, in which pottery was fired with coal. They were outlawed by the Clean Air Act of 1956 and redundant from July 1963. But it’s more complicated than you might think!

Full description of Potteries bottle ovens and kilns

Here is a really good and succinct description, of the Potteries bottle oven and bottle kiln.

Courtesy of Gladstone Pottery Museum, Longton. (Link to the museum site here> https://www.stokemuseums.org.uk/gpm/

Bottle oven is a generic term applied to a variety of brick-built, coal-fired ovens and kilns used in the north Staffordshire pottery industry. The name derives from the characteristic shape of the hovel or stack utilised by such structures, but covers a range of different types, some of which fired wares to a biscuit or glost state (these were known locally as ovens), with others (specifically referred to as kilns in the Potteries) used in the decorating process (muffle kilns), or the preparation of raw materials for ceramic bodies (calcining kilns) or glazes and colours (frit kilns). There was also variation in the means of construction. For example, not all types had independent hovels, many being enclosed within buildings and having the stack (which equated to the ‘neck’ of the bottle) constructed directly on top of the firing chamber or supported on an outer ‘skeleton’ structure. In addition, by the late 19th century, both up- and down-draught (in which heat was re-circulated around the firing chamber) types were in use within the industry.

STRUCTURE

The simplest type of bottle oven (the hovel oven) consists of two main parts:The outer part

The distinctive bottle-shaped chimney is known as the hovel. This could be up to 70 feet (21m) high. The bottle shape, with its wide base and narrow neck, evolved to accommodate the firing chamber together with room for men to work, and for materials and equipment. The shape of the tapering chimney was good for creating draught which aided the firing process and helped to take away smoke. It also improved protection from bad weather.

|

| Bottle oven hovels at Gladstone Pottery Museum Photo: source unknown Date: 1975 |

The inner part

This is the firing chamber. It is a cylindrical structure with a domed roof called the crown. Its walls are about 12" (30cm) thick. Tight iron bands, known as bonts, run right round the circular oven at about 12" (30cm) intervals to strengthen it as it expands and contracts during firing. A doorway, called the wicket, was just large enough for a man with a saggar on his head to pass through. The wicket is surrounded by a stout iron frame.

Around the base of the firing chamber are firemouths (the exact number depends on the size of the oven) in which fires were lit for the firing. Inside the firing chamber there is a small chimney, called a bag, over each firemouth. The bags carried hot gases and intense heat from the fire into the interior. Flues underneath the sloping floor of the chamber, leading from each firemouth, distributed the heat throughout the inside. In the centre of the oven floor is the well hole.

Each bottle oven had its own character and the fireman had to learn how best to work with them, to control and cajole the way they performed and fired.

All were intermittent since the firing process occurred periodically, at regular (and sometimes irregular) intervals. The oven was filled with pottery, fired to temperatures as high as 1450°C for some pottery recipes, and then cooled and drawn. The process would then start all over again. Busy factories aimed to fire their bottle ovens regularly and on the same days every week. Neighbouring households would know that they should not hang out their washing to dry on firing days if they were to avoid smoke smuts.

Pottery usually needs firing several times during its manufacture. Different ovens and kilns were needed for each type of firing. Depending on its output, a factory could have 25 ovens or more. Within a factory, ovens were not situated to any set plan. They may have been grouped around a cobbled yard, similar to the layout at Gladstone, or in a row. Sometimes they were built into the workshops with the upper part of the bottle-shaped chimney protruding through the roof. The chimney of this type of oven was sometimes built directly onto the shoulder of the firing chamber and this was known as a stack-type oven.

Around the base of the firing chamber are firemouths (the exact number depends on the size of the oven) in which fires were lit for the firing. Inside the firing chamber there is a small chimney, called a bag, over each firemouth. The bags carried hot gases and intense heat from the fire into the interior. Flues underneath the sloping floor of the chamber, leading from each firemouth, distributed the heat throughout the inside. In the centre of the oven floor is the well hole.

Each bottle oven had its own character and the fireman had to learn how best to work with them, to control and cajole the way they performed and fired.

All were intermittent since the firing process occurred periodically, at regular (and sometimes irregular) intervals. The oven was filled with pottery, fired to temperatures as high as 1450°C for some pottery recipes, and then cooled and drawn. The process would then start all over again. Busy factories aimed to fire their bottle ovens regularly and on the same days every week. Neighbouring households would know that they should not hang out their washing to dry on firing days if they were to avoid smoke smuts.

Pottery usually needs firing several times during its manufacture. Different ovens and kilns were needed for each type of firing. Depending on its output, a factory could have 25 ovens or more. Within a factory, ovens were not situated to any set plan. They may have been grouped around a cobbled yard, similar to the layout at Gladstone, or in a row. Sometimes they were built into the workshops with the upper part of the bottle-shaped chimney protruding through the roof. The chimney of this type of oven was sometimes built directly onto the shoulder of the firing chamber and this was known as a stack-type oven.

“The ovens are the most important part of the potter’s plant, and it is on their successful management that the result of the business will largely depend. Good biscuit ware is absolutely necessary to make good glost ware and yet if the glost firing is not up to the mark the ware will be inferior, no matter how good the biscuit may have been. It is on these processes that the ware depends for its solidity, brilliancy of appearance, and durability; and it matters little what care may have been bestowed in the potting, glazing, and decoration of the pieces if the firing is not satisfactory. It is in this department that more money is lost than in any other, and any time given up to the correction of defects, or to the lessening of breakage and loss in the ovens, is indeed well spent.”

Extract from: Notes on the Manufacture of Earthenware

by Ernest Albert Sandeman, 1901

DESCRIPTION and TYPES?

The name 'bottle oven' was derived from their particular shape and not as a reference to the manufacture of bottles! Some ovens were used for firing pottery to biscuit and then the glost stages. These huge ovens could hold as many as 3000 dozen (36,000) pieces of pottery at a time. Some, much smaller and known as muffle kilns, were used for firing applied decoration to the ware to render it permanent. Smaller still were hardening on muffle kilns.

Ovens and kilns were described by the way they operated - either as updraught or downdraught or muffle. Some were used for calcining flint or bone for use as components of the pottery body recipe.

Some were described as 'oven-n-ovel' (oven and hovel, or more simply hovel oven) where the firing chamber stands in the centre of the separate circular hovel which was, essentially, the chimney stack. These could be entirely free-standing or partially attached to an adjacent workshops for instance, the placing or saggar shop.

Others were described as stack ovens where the oven and the bottle-shaped stack were built together. In this case, the bottle-shaped chimney was built straight onto the top of the shoulder of the oven. This type became part of the entire structure of the factory, with the chimney rising through its roof. Some ovens were a combination/variation of both hovel oven and stack oven and known as skeleton ovens.

More about oven types and shapes here>

"Some are prim and severe, spinsterish even, in line and appearance;

others peculiarly curvaceous. The immense heat of the firing distorted their swelling curves, great fissures and cracks appeared, drastic surgery was necessary to preserve them, the brickwork was renewed and their great bellies were strapped round with girdles of iron to save them from collapse." From an essay by Reginald G. Haggar here>

HOW MANY and WHAT'S LEFT?

Gladstone Works (now, a museum of the industry) has five of those still in existence, and there are two next door at the Roslyn Works. So in a this very small area of Longton, the southern-most town of Stoke-on-Trent, there are seven magnificent bottle ovens, that's 15% of all those remaining in the Potteries. A very special place.

This grouping is unique, saved at the eleventh hour in 1971. more here>

The Gladstone Pottery was restored and opened to the public as a museum officially on 24 April 1975 by The Duke of Gloucester. In the years since the museum opened its huge and magnificent ovens have undergone restoration and all five at Gladstone can be explored.

The people of the Potteries who lived and worked in these buildings invariably despise them. They created ill-health, terrible lung disease and early death. They filled the atmosphere of the area with thick black smoke and "golf ball-sized" smuts. They ruined brickwork and paintwork and etched windows with the acid rain which they created. They blackened churches and municipal buildings.

"Some of them were respected, others were feared,

and some were absolutely hated and were known by rude names."

From an essay by Sir George Wade here>

| Longton skyline with Gladstone Pottery circled Photo: unknown source Date: 1953 |

HISTORY OF THE STAFFORDSHIRE POTTERIES by SIMEON SHAW, 1829

A description of the filth produced

"The vast volumes of smoke and vapours from the ovens, entering the atmosphere, produced that dense white cloud, which from about eight o'clock till twelve on the Saturday morning, (the time of firing-up, as it is called,) so completely enveloped the whole of the interior of the town, as to cause persons often to run against each other; travellers to mistake the road and strangers have mentioned it as extremely disagreeable, and not unlike the smoke of Etna and Vesuvius."| Bottle ovens and smoking chimneys in the Potteries landscape Photo: source unknown Date: Early 1950s |

THE UPDRAUGHT BOTTLE OVEN

A bottle-shaped structure, built from brick, in which pottery was fired. It most commonly consisted of two main parts, an outer hovel and an inner oven.The outer, which is the bottle shaped part, is known as the hovel. This could be up to 70 feet high, but never less than 60 feet according to the Borough of Hanley Works Committee Minutes – 14 February 1877. The hovel acted as a chimney taking away the smoke, creating an up-draught and protecting the oven inside from the weather and uneven draughts.

|

| Gladstone Pottery Museum - updraught bottle ovens in the cobbled yard Photos: Phil Rowley Date: 2015 |

There is a narrow gap between the hovel and its inner part which is called the firing chamber.

The firing chamber is a round, robust brick built structure with a domed roof, called the crown, and its walls are approximately 1 foot thick. Iron bands, known as bonts, run right round the circular oven at intervals, to strengthen it as it expands and contracts during firing.

Around the base are firemouths - the exact number depends on the size of the oven - in which fires were lit for the firing.

Inside the firing chamber, over each firemouth, is a bag (a small chimney) which carries most of the intense heat from the firemouth into the setting inside.

Pottery may need to be fired up to 10 times during its manufacture and different ovens and kilns were needed for each type of firing. Depending on the output of each factory, a single works could have anything from one to 25 ovens, and up to 40 on very big factories (Spode, in Stoke, had 37 in 1843). Gladstone Pottery has five. At the Middleport Pottery of Burgess and Leigh, near Burslem, just one remains but at its height the factory had seven.

Within a factory, ovens were not situated to any set plan. They may have been grouped around a cobbled yard (as a Gladstone Pottery) or in a row, or rows. Sometimes they were built into the workshops with the upper part of the hovel protruding through the roof. The stack (chimney) of such ovens was usually built on the shoulder of the oven itself.