Earthenware and Bottle Ovens

Part of an essay for CLAYART in WALES, 2006

By Kathy Niblett BA AMA FRSA

Our beautiful body, [earthenware] shaped and possibly decorated, is nothing until baked.

A firing chamber and a fuel are needed to raise the clay to a temperature above about 600ºC when the irreversible chemical changes take place and the soft mud becomes a brittle, hard pot. Dr. Plot described the ovens he saw in use in Burslem in 1686, ordinarily above 8 foot high, and about 6 foot wide, of a round copped forme. He was describing the business part, the domed, 'beehive' shaped firing chamber which was protected by the addition of a hovel in the shape of a bottle, as the 18th century progressed.

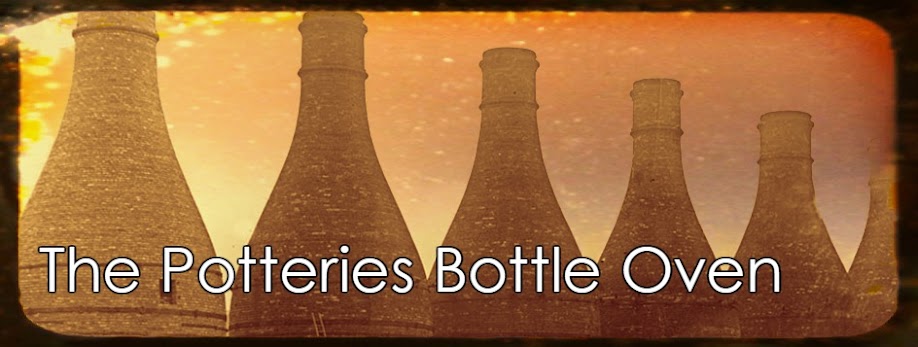

Bottle ovens were the iconic building for firing ceramics, offering storage and working space for fuel, ware and saggars and protection for all, including the firing chamber itself. The tall chimney of the bottle form was ideal for venting the smoke and other gases.

It is thought that wood was used in the early days of the 'round copped forme' but in Staffordshire the abundant supply of coal made pottery production a natural industry of the area, with the consequence of black smoke, produced whenever the firemouths were baited or fed with coal. It is important to realise that to fire one ton of domestic clay-ware in a bottle oven between seventeen and twenty tons of coal would be used.

A firing chamber and a fuel are needed to raise the clay to a temperature above about 600ºC when the irreversible chemical changes take place and the soft mud becomes a brittle, hard pot. Dr. Plot described the ovens he saw in use in Burslem in 1686, ordinarily above 8 foot high, and about 6 foot wide, of a round copped forme. He was describing the business part, the domed, 'beehive' shaped firing chamber which was protected by the addition of a hovel in the shape of a bottle, as the 18th century progressed.

Bottle ovens were the iconic building for firing ceramics, offering storage and working space for fuel, ware and saggars and protection for all, including the firing chamber itself. The tall chimney of the bottle form was ideal for venting the smoke and other gases.

It is thought that wood was used in the early days of the 'round copped forme' but in Staffordshire the abundant supply of coal made pottery production a natural industry of the area, with the consequence of black smoke, produced whenever the firemouths were baited or fed with coal. It is important to realise that to fire one ton of domestic clay-ware in a bottle oven between seventeen and twenty tons of coal would be used.

Pots were subjected to awful conditions in the chamber. Temperature, over many hours, smoke and gases, particularly sulphur given off by some coals, could seriously injure their surfaces and to avoid this, ware was placed in protective boxes, made of marl, not clay and called saggars. Saggars were stacked in bungs, tall columns in the firing chamber, attention being paid by the cod placer, the chief placer, to the siting of contents according to the hot spots.

As Robert Plot said: they doe not expose them to the naked fire, but put them in shragers, … to preserve them from the vehemence of the fire, which else would melt them downe, or at least warp them.

Bottle ovens were built all over Britain, wherever pottery was made. In 1945 there were about 2000 bottle shaped structures in Stoke-on-Trent, not all potters' ovens, some were structures used by potters' millers in the preparation of raw materials, flint and animal bone.

The Clean Air Act of 1956, enacted in 1958, sounded the death-knell of the coal-consuming, black-smoke belching giants, which dominated the landscape of The Potteries. Their architecture gives a romantic appeal but to work with a bottle oven was back-breaking and seriously injurious to the health of workers and the people of the district.

Arnold Bennett described their impact well in his novel The Old Wives Tale:

The Clean Air Act of 1956, enacted in 1958, sounded the death-knell of the coal-consuming, black-smoke belching giants, which dominated the landscape of The Potteries. Their architecture gives a romantic appeal but to work with a bottle oven was back-breaking and seriously injurious to the health of workers and the people of the district.

Arnold Bennett described their impact well in his novel The Old Wives Tale:

The Five Towns … are unique and indispensable. … the architecture of the Five Towns is an architecture of ovens and chimneys; … its atmosphere is as black as its mud; it burns and smokes all night, … it is unlearned in the ways of agriculture, never having seen corn except as packing straw … it comprehends the mysterious habits of fire and pure, sterile earth; … it lives crammed together in slippery streets where the housewife must change white window-curtains at least once a fortnight if she wishes to remain respectable; … it exists – that you may drink tea out of a teacup and toy with a chop on a plate.

In Stoke-on-Trent today, forty-seven bottle shapes remain to tell the tale of past glories and horrors. Although all are Listed, many are in a dreadful condition and demolition by neglect will surely follow. There are honourable exceptions and owners take their responsibilities very seriously. It is no easy task to maintain a bottle oven since the shape and size (up to 70 feet high) offer challenges to all but steeplejacks. How can you 'weed' a garden in the sky? These 'buildings' were always warm so that now rain and frost take their toll with every passing winter. No bottle ovens survive in Tunstall, the most northerly of the Six Towns. The only down draught survivors in the City, are in a perilous state, in Burslem.

The last commercial firings of bottle ovens in Stoke-on-Trent took place in the-mid 1960s. In 1978 a coal firing was arranged by Gladstone Pottery Museum so that a film record could be made before all structures were unsafe and whilst the men who had the skills could revive their talents and direct a team of ignorant volunteers. It was an amazing week.

© Kathy Niblett 2006

Kathy Niblett has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

The bottle oven which is most easy to describe and understand is basically a structure in two parts.

The firing chamber is a tall cylinder built with refractory (fire-resistant bricks) with a domed roof called the crown. It has one doorway known as a wicket or the clammins and around the base are the fire mouths.

This firing chamber is protected by the hovel - the bottle shaped, brick-built structure which gives it its name. Its shape is exactly like the old fashioned milk bottle with straight sides from ground to above the crown .

Very few processes were carried on within the hovel and so, little space was required.

The hovel oven could be used to fire both biscuit and glost ware - the first and second firings of undecorated product. This type of oven is likely to be an up-draught oven.

From the fire mouths there are flues running under the floor to the centre of the firing chamber and on the inner wall immediately above the fire mouths are the bags, which are like small chimneys. The flues and the bags ensure that the heat is distributed to all parts of the firing chamber. Naturally the spots near to the bags are hotter than in other parts. One of the skills of the cod placer, the man in charge of placing the oven, was to place the right product in the right place according to its need for a hotter or cooler firing.

The floor of the firing chamber rises slightly to the centre where all the under-floor flues meet in the well-hole. Above this hole a chimney is built, called the pipe bung, as the oven is filled. Saggars, without bases, are placed one on top of the other. The heat, gases and smoke rise through the setting and escape through the crown and up the chimney.

Kathy Niblett

Author of 'The Mighty Bottle Oven' 1998, City Museum and Art Gallery, now Potteries Museum and Art Gallery.

© Kathy Niblett 2006

Kathy Niblett has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

The Mighty Bottle Oven

A description by Kathy Niblett BA AMA FRSA

February 1998

The bottle oven which is most easy to describe and understand is basically a structure in two parts.

The firing chamber is a tall cylinder built with refractory (fire-resistant bricks) with a domed roof called the crown. It has one doorway known as a wicket or the clammins and around the base are the fire mouths.

This firing chamber is protected by the hovel - the bottle shaped, brick-built structure which gives it its name. Its shape is exactly like the old fashioned milk bottle with straight sides from ground to above the crown .

Very few processes were carried on within the hovel and so, little space was required.

|

| Cross section through an updraught bottle oven Shows flues from bags to well hole Image: Phil Rowley |

From the fire mouths there are flues running under the floor to the centre of the firing chamber and on the inner wall immediately above the fire mouths are the bags, which are like small chimneys. The flues and the bags ensure that the heat is distributed to all parts of the firing chamber. Naturally the spots near to the bags are hotter than in other parts. One of the skills of the cod placer, the man in charge of placing the oven, was to place the right product in the right place according to its need for a hotter or cooler firing.

Kathy Niblett

Author of 'The Mighty Bottle Oven' 1998, City Museum and Art Gallery, now Potteries Museum and Art Gallery.